ADVICE TO APPLICANTS

RESEARCH

HIGHLIGHTS

Lab director

Peter Chesson

Post-doctoral Associates

Lina Li

Graduate Students

Galen Holt

Chi Yuan

Yue (Max) Li

Pacifica Sommers

Simon Stump

Nick Kortessis

Recent PhDs

Megan Donahue

Anna Sears

Jessica Kuang

Adam Miller

Maureen Ryan

Recent Postdocs

Andrea Mathias

Jessica Kuang

Danielle Ignace

Undergraduate Students

Elieza Tang

Krista Cole

Friends of the Lab

Andrea Mathias

Adam Miller

Charlotte Lee

Brett Melbourne

Kendi Davies

Maureen Ryan

Scott Stark

Yun Kang

Graduation Photos

|

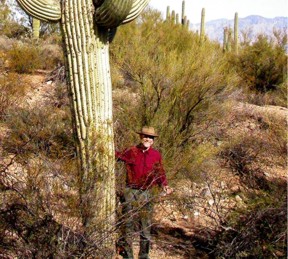

Our study systems

Some of us are fond of studying communities of

annual plants. We find these in the deserts of Arizona and Eyre

Pennisula

(South Australia), in the vernal pools of the Central Valley of

California,

and in the coastal

swales near Bodega Bay. We also study

perennial herbs in the

understorey of Eucalypt forests in Australia. Some of us

are aquatic in orientation studying aquatic insects and amphibia in

ponds and streams, or invertebrates in

marine environments.

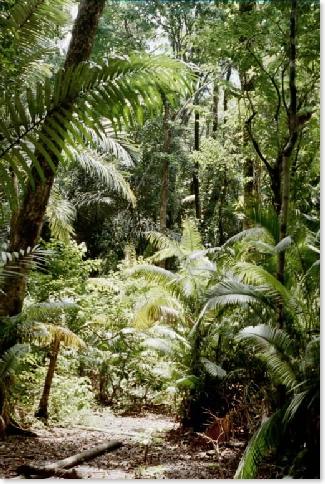

There are lots of systems that we think about

but do not collect data on ourselves, at least not right now. These

include coral

reef fish communities, tropical forests, and host-parasitoid systems.

Our tools

For studies of natural systems, we are

developing new classes of quantitative tools to test coexistence

mechanisms and hypotheses about dynamics of populations and communities

subject to spatial and temporal variation. Then we go out into

the field to count, measure, and manipulate.

For theoretical studies, we use math and

computers. We are fond

of probability and statistical theory. We also get into

differential equations

and Fourier transforms.

|

Our questions

Ecological

diversity

and its maintenance

The diversity of life is the wonder of the world. It inspires us, but

it challenges us to explain it too. Sadly also, diversity is under

threat on many fronts from human activities. To confront this threat we

need better understanding of the maintenance of diversity. The

diversity of life involves ecological diversity: different organisms do

different things in the

aid of their lives and their offspring. Some differences are subtle.

Some differences are gross. How do these differences arise, and what is

their role in maintaining diversity? How do the attributes of species

predict community change with environmental change?

General

testable community theory

To

understand diversity maintenance, we need theory for ecological

communities. It must be realistic enough to contain the key features

behind diversity maintenance in nature, it must be general enough to be

robust to variation in minor features, and it must be testable too.

Nature has many complexities, not the least of the which are the many

different species in any ecological community interacting with one

another in many different ways. The environments of organisms are

complex too. They vary greatly in space and time interacting with the

lives of organisms and their relationships with others. We try to rise

the challenge of this complex work, seeking theory that defines general

principles, and shows how to test them in specific contexts. We make it

quantitative, operational

and testable in practice. Then we go out and test it.

Variation and

scale

Ecological systems are characterized by

variability on all scales. Individual organisms vary one from another,

their environments vary every which way, populations fluctuate over

time and in space, communities vary and change in

composition. We ask how variation affects the way ecological systems

work. On the individual level, life histories may be adapted to

variation, ready to take advantage opportunities, but hedging against

uncertainties. Life-history properties, and the variation moulding

them,

have consequences for population dynamics and species interactions.

Population dynamics take different forms on different temporal and

spatial scales. Spatio-temporal niche differentiation arises from

taking advantage of opportunities in space and time. Species diversity

is promoted, interactions are stabilized, ecosystem functioning is

affected, and invasion resistance develops. We develop the mathematical

theory behind these ideas. We develop the methods to test them, and

then we go out and test them.

|

Our

Concepts

Research Highlights

Community

dynamics in time and space

Natural communities

inhabitat a world of great complexity in time and space. The physical

environment has many spatial complexities in its topography, hydrology

and soils. And it changes over time: organisms experience

varying weather and climatic changes on many scales interacting in a

variety of ways with spatial environmental varation. Various

processes, not just the physical environment, but also interactions

between organisms, cause their densities to vary greatly in space and

time too. It has often been hypothesized that these different

kinds of

variation have important roles in diversity maintenance. But what

are those roles? Development of mathematical models with such

complexities is not easy, and so it is perhaps not surprising that much

mathematical theory, even if it addresses density variation in time or

space, rarely includes variation in the physical environment. The

theory coming from this lab is different. We have embraced

environmental complexity, and gathered the mathematical tools necessary

to study it. The result is a comprehensive multiscaled theory of

diversity maintenance that includes the standard equilibrium theory as

a special case. This work has led to the recognition of several new

species coexistence mechanisms including the

storage effect, nonlinear

competitive variance, and fitness-density

covariance.

Multitrophic

diversity maintenance

The study of diversity maintenance mechanisms has

traditionally focused on competition, with predation mostly seen as

modifying what competition does. However, there is growing

evidence that predation and competition can have very similar effects

on the maintenance of species diversity. This similarity of action

relies on the observation by Bob Holt (University of Florida) that both

predation and competition can lead to mutually negative indirect

interactions between species. Of most importance, such mutually

negative indirect interactions apply not just between species but also

to different individuals within the same species. Theoretical

consequences of these facts mean that predation and competition each

have the potential to limit diversity or promote diversity. For

both predation and competition it all depends on the extent to which

within species interactions outway between species interactions.

When predation and competition have similar strengths for a given set

of

interacting species, the overall outcome for diversity |

maintenance may

represent a compromise between the separate tendencies of predation and

competition in the given circumstances. In other cases, new mechanisms

promoting diversity arise from the interaction between predation and

competiton. If one mechanism is much stronger than the other, the

tendency of the stronger mechanism prevails.

One major thrust within the lab explores these

various ideas in

general models and in models of specific systems, such as annual plant

communities. We combine them with other thrusts on the effects of

environmental variation in space and time, and we ask also how trophic

cascades affect the maintenance of diversity in any given trophic level.

Testing

species coexistence mechanisms

One of the biggest

challenges in community ecology is explaining

patterns of species diversity. We cannot hope to explain these patterns

unless we understand mechanisms of species coexistence. Although

there are numerous

hypotheses about species coexistence, few have been demonstrated in

nature with any degree of confidence.

Our theoretical

developments have recently led to powerful new ways of testing

species coexistence mechanisms. These tests use field

manipulations to test directly for mechanism functioning. Unlike

many other tests, which merely indicate consistency with mechanisms,

these tests are definitive, and thus provide high confidence that the

mechanism is working in the system. Most empirical studies in the

lab are using these new methods.

The

basis of these

new methods is the quantification of mechanism

strength and the functional components of mechanisms discussed

next.

Quantifying

mechanism strength in terms of

functional components

How do species coexistence

mechanisms work? And how do we know how strong they

are? Our lab has developed measures

of mechanism strength based on how much a mechanism

increases the rate of recovery of a species from low density. In

nature, species always fluctuate, and if they are to remain in a

community, they must recover from their low excursions. Focusing

on

these recovery rates, we have found ways of quantifying mechanism

strength in terms of the |

functional

components that define the

mechanism. This has led not only to a big increase in

understanding of

mechanism functioning, but also powerful

new

ways of testing mechanisms.

Multiple

mechanisms, mulitple scales

Most people expect that most natural communities

have multiple mechanisms of diversity maintenance in operation.

Moreover, these mechanisms are likely to work on a variety

of

scales. How do we understand systems with such complexities? The method

of

quantifying mechanism strength discussed above allows us to

partitioning

the recovery rate into the contributions from different mechanisms and

the contributions from

different scales in space

and time.

This allows

comparative contributions of the various applicable mechanisms to be

assessed,

facilitating understanding both in models and in nature.

The

scale transition

in theory and practice

Much progress has been made in recent years in the

development of models of communities subject to spatial and temporal

variability. So active is the work on the spatial front that it

is regarded as a new field, spatial ecology. But a daunting

challenge is how you test spatial ecology in the field. An

equally daunting challenge is how you achieve general understanding of

spatial and temporal mechanisms. Developments in this lab over

many years have led to a body of work called scale transition

theory,

which explains spatial and temporal ecology in terms of interactions

between nonlinear population processes and variation in space and

time. Of most importance, this work leads to ways of testing

spatial and temporal ecology, which are general, powerful and pratical.

Ecological

complexity

The work discussed here provides one route to understanding ecological

complexity. It takes a complex dynamic phenomenon and asks what

is it about this complexity that is relevant to critical questions like

species

coexistence, population

persistence, and population

stability. The results are statistical measures of complexity

that are functional predictors of the outcomes to these questions.

|

Peter Chesson

Community

Processes

in Variable Environments

Community

Processes

in Variable Environments

The natural world is inherently variable. The

physical environment varies on all scales and so do the organisms

inhabiting it. Organisms

are adapted to this variability, not merely hedging against uncertainty

but

taking advantage of opportunities that variability brings. My main

interest is how the adaptation of organisms to variability promotes

species diversity and affects ecosystem functioning. I do this

primarily theoretically by developing

mathematical models using probability theory and the methods of

theoretical

statistics. Recent research topics have involved neighborhood

competition

models, community assembly, invasion resistance, multitrophic diversity

maintenance, life-history theory and the various

manifestations

of temporal and spatial niches, also known as the storage effect and

relative

nonlinearity of competiton. In addition, I am involved with field

projects

on annual plants and herbaceous perennial plants. Other systems that

are

foci of theorizing are coral reef communities, tropical forests, and

communities

in mediterranean climates.

Advice

to applicants...

Some recent publications

Chesson,

P. 2000. Mechanisms of maintenance of species diversity. Annual Review

of Ecology and Systematics 31, 343-66.

Chesson,

P. 2000. General theory of competitive coexistence in spatially varying

environments. Theoretical Population Biology 58, 211-237.

Chesson, P. 2001.

Metapopulations. Pp 161-176 in Encyclopedia of

Biodiversity, Vol 4, Simon A. Levin, ed, Academic Press.

Shea,

K., Chesson, P. 2002. Community ecology theory as a framework for

biological invasions. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 17, 170-176.

Chesson,

P.,

Peterson, A.G. 2002. The quantitative assessment of the benefits of

physiological integration in clonal plants. Evolutionary Ecology

Research 4, 1153–1176.

Chesson,

P. 2003. Quantifying and testing coexistence mechanisms arising from

recruitment fluctuations. Theoretical Population Biology 64,

345–357.

Chesson,

P., Gebauer, R. L. E., Schwinning, S., Huntly, N., Wiegand, K.,

Ernest, S. K. M., Sher, A., Novoplansky, A., and Weltzin,

J.F. 2004. Resource pulses, species interactions and diversity

maintenance in arid and semi-arid environments. Oecologia 141,

236 - 253.

Facelli,

J.M., Chesson, P., Barnes, N. 2005. Differences in seed biology of

annual plants in arid lands: a key ingredient of the storage

effect. Ecology 86, 2998-3006.

Chesson,

P., and Lee, C.T. 2005. Families of discrete kernels for modeling

dispersal. Theoretical Population Biology 67, 241-256.

Chesson,

P., Donahue, M., Melbourne, B., Sears, A. 2005. Scale

transition theory for understanding mechanisms in

metacommunities. In Holyoak, M, Leibold, M.A., Holt, R.D., eds,

Metacommunities: spatial dynamics and ecological communities, pp

279-306

Sears,

A.L.W., Chesson, P. 2007. New methods for quantifying the

spatial storage effect: an illustration with desert annuals.

Ecology 88, 2240-2247

Chesson,

P. 2008. Quantifying and testing species coexistence

mechanisms. Pp 119 – 164 in Valladares, F., Camacho, A., Elosegui, A.,

Estrada, M., Gracia, C., Senar, J.C., & Gili, J.M., ed. “Unity in

Diversity: Reflections on Ecology after the Legacy of Ramon Margalef.”

Chesson,

P, and Kuang, J.J. 2008. The interaction between predation and

competition. Nature 456, 235-238

All

publications

pchesson@u.arizona.edu

Back to top

Lina Li

Communities in varying environments

Coexistence in a temporally varying environment is

predicted to arise when species differ in their temporal patterns of

resource consumption. However, key to this outcome is coupling of

resource consumption and resource availability. High resource

consumption rates, due to favorable environmental conditions, are

expected to draw down resources, causing high competition. The

phenomenon is called covariance between environment and competition

(covEC). For coexistence to occur, covEC must be weaker for a species

perturbed to low density (an “invader”) compared to an unperturbed

species (a “resident”). However, these outcomes have not been

thoroughly investigated in models. Instead, the formulation of

models often implicitly includes them. Thus, the theory is

incomplete because there is no satisfactory theory of this key

component, covEC. Moreover, it has been suggested detecting covEC in

nature provides a powerful means of testing coexistence by the storage

effect. The phenomenon of covEC therefore requires a thorough

theoretical understanding. Here we extend the MacArthur

consumer-resource model to varying environments. The explicit

resource dynamics in the MacArthur model allow a theory of covEC to be

developed. Our approach was to develop quantitative measures of factors

contributing to covEC, and studying their effects in computer

simulations. We found that relative speeds of resource

consumption, consumer

dynamics and environmental variation have major effects on covEC.

Resource speed by far had the dominant effect and can be divided into

two major components, resource amplitude, and resource phase relative

to consumers. Resident covEC is maximal when resource amplitude

is greatest and phase relative consumers is zero, and this is achieved

when resources turn over rapidly, most strongly promoting coexistence

by the storage effect. These results allow us to address the

fundamental ideas of Hutchinson’s Paradox of the Plankton. While

they do show that seasonal environmental variation can promote

coexistence of consumers on limited resources, it produces very

different predictions about time scales of environmental change and

consumer dynamics compared with Hutchinson. Contrary to

Hutchinson’s predictions we find that slow consumer dynamics are

favorable to coexistence and do not lead to averaging of environment

fluctuations, nullifying their effects. Critical to coexistence is

factors strengthening covEC for residents, found here to be fast

resource dynamics, not intermediate consumer dynamics.

linali19800815@yahoo.com

Back to top

Galen Holt

Empirical study of

ecological concepts

Empirical study of

ecological concepts

I am interested in population and community dynamics in

variable

environments, especially how environmental heterogeneity enhances

persistence. I have a field system in streams in the Catalina

Mountains, focusing on the persistence of various aquatic organisms in

pools. I have worked also on models and experiments for

understanding annual plant coexistence. Below I have included the

abstract of a talk I gave at the ESA 2008 on this topic.

Species-specific

germination speed and

coexistence in a desert annual plant community.

Desert annual pants are frequently the subjects of

coexistence studies with a focus on the role of environmental variation. Germination rates are observed to vary

substantially

over time forming the basis of the storage-effect coexistence mechanism. Laboratory germination studies have

reproduced some of this variation, but do not replicate the full range

of

conditions found in the field. Here we

discuss one aspect of field variation that potentially has a major

effect on

plant species coexistence, but has been neglected in the past.

Experimental and

observational data from the desert annual plants at our field site near

Portal,

AZ show distinct species-specific differences in the speed of

germination

following rainfall. This indicates an important and previously

unexplored

opportunity for covariance between competition and the environment, a

key

quantity for coexistence by the storage effect. Most seeds are at or

near the

surface, and so moisture at the soil surface is critical for

germination.

Duration of this moisture varies greatly due to duration, and spacing

of

rainfall events, and also due to solar radiation, temperature, humidity

and

wind following these events. Field observations and laboratory

experiments show

that the observed differential germination speed is strong enough to

lead to different

species dominating due to different durations of soil moisture. Thus,

variation

in duration of surface soil moisture potentially contributes

substantially

yearly variation in the species composition of the annual plant

community. Using

data on germination speed from field observations and germination

experiments

in the lab, we built a model linking fluctuations in surface soil

moisture and

species’ germination speeds to predict the crop of plants resulting

from

specific rainfall patterns. Our model implies that the interaction of

species-specific germination speed with variation in soil moisture

makes a

major contribution to the storage-effect coexistence mechanism in this

community.

For example, species that germinate quickly have greater opportunity to

take

advantage of short-duration rainfall and surface soil moisture, while

other

species require a longer period of surface soil moisture to

successfully

germinate, but may be superior competitors once germinated.

Incorporating the

interaction between germination speed and the duration and spacing of

rainfall

greatly expands the opportunities for species coexistence in this

community.

This increased understanding of the factors controlling community

composition

also provides a more refined understanding of the long-term stability

of

species composition.

gholt@email.arizona.edu

Back to top

Chi Yuan

Models of species coexistence in a

temporally varying environment

I study mathematical models to understand how environmental

variation affects species coexistence. So far, I have studied the

coexistence mechanism called

relatively nonlinear competitive variance

(aka relative nonlinearity)

in the lottery model. I found that the storage effect is a much

stronger mechanism than relative nonlinearity. However, relative

nonlinearity does have important effects if some species

have large adult death rates while other species have small adult

death rates. I want to study other models and other mechanisms in my

PhD work

Yue (Max) Li

Yue (Max) Li

Diversity maintenance

mechanisms in different systems

I am interested in how the mechanisms of diversity

maintenance

differ between different systems, such as deserts and tropical

forests. Recently, I have been focusing on frequency-dependent

predation as a coexistence mechanism with a view to understanding how

it might be studied in different ecosystems.

liyue@u.arizona.edu

Back to top

Pacifica

Biodiversity Patterns

I am interested exploring

patterns

of biodiversity empirically and theoretically.

Currently, I am incorporating predator

avoidance

(indirect predator effects) into multi-trophic models of population

dynamics

to look at its effects on coexistence between similar species. I

am beginning empirical work with a community of aquatic insects in

mountain streams.

Back

to top

Simon

Effect

of pathogens on species

coexistence

I am fascinated by the question of what allows

intra-guild

competitors to coexist,

and hope to study this phenomenon both theoretically and empirically.

Right now the specific question I am asking is,"How do

parasites, disesases, and other

pathogens affect coexistence?" I want to understand when they promote

coexistence, and when (if ever) they undermine it. I am still

developing a research plan, but I think

my model organisms

will be desert annual plants and parasitic fungi.

My

key interest is understanding

fluctuation-dependent coexistence mechanisms focusing on how the

mechanism, relatively nonlinear competitive variance workswith multiple

competitive factors.

My

key interest is understanding

fluctuation-dependent coexistence mechanisms focusing on how the

mechanism, relatively nonlinear competitive variance workswith multiple

competitive factors.

Friends of

the Chesson Lab

former members

Danielle Ignace

Physiological Ecology of Plant Invasions

I am studying the causes of the dramatic

irruption of the Eurasian invasive plant, Erodium cicutarium, in the San

Simon Valley of southeastern Arizona. It many areas, it is now

95% or more of

the winter annual plant biomass, up from a miniscule

presence away from roads in the 1980s. At the same time, native

winter annual plants have become very rare and are showing changes in

species composition. This new monoculture potentially has

profound implications for biodiversity, habitat quality, ecosystem

functioning and forage quality of the rangeland. My research applies a

physiological, ecosystem, community and theoretical approach to

understanding the characteristics associated with the irruption and

distribution of E. cicutarium

and its impacts for biodiversity in the San Simon Valley.

ddignace@email.arizona.edu

Back to top

Jessica

Kuang

Interactions

between Predation and Resource Competition

To

study problems in community ecology I

have been investigating mathematical models of species interactions

which take the form of nonlinear multidimensional Markov processes in

continuous space. The basic questions concern species coexistence,

which means finding conditions under which no species density converges

to zero with time. The particular mathematical techniques are invasion

analysis and quadratic approximations of the model. The

particular

ecological problem studied is the effect of a common enemy ("apparent

competition") on the coexistence of species that compete for

common resources. Biodiversity and coexistence are well studied by many

ecologists over the past century; however, this is the first study

which consider both resource and apparent competition in a stochastic

model.

Jessic

Kuang's website

jjkuang@u.arizona.edu

Back to top

Andrea Mathias

Non-equilibrium dynamics and species coexistence

Non-equilibrium dynamics of natural ecosystems

have

a major

role in generating and maintaining biodiversity. The main objective of

my

research is the mechanistic understanding of this role in both

ecological and evolutionary context. In particular I am interested in

life history evolution with frequency dependent selection in temporally

fluctuating and spatially heterogeneous environments.

So far I have studied the conditions for the

development of polymorphisms in initially monomorphic populations

leading to adaptive speciation, allowed by different regimes of spatial

and temporal heterogeneity (Mathias et al., 2001; Cheptou and Mathias,

2001; Mathias and Kisdi, 2002).

Currently I am studying the competitive

mechanisms

promoting coexistence in a multiple resource competition model of

phytoplankton species, in the context of a generalized theory (Chesson,

1994; Chesson and Huntly, 1997; Chesson, 2000a, b). In this model the

growth rate of the species is a non-linear function of the limiting

factors, which can result in endogenously created oscillations of

density. This mechanism has enormous stabilizing potential

for the coexistence of a surprisingly high number of species on few

resources.

My goal is to understand the details of the role of relative

nonlinearity

in species coexistence, which has not yet been investigated

sufficiently

in this case.

In the future I would like to extend the theory

of

species coexistence in competitive systems to life history evolution in

order to understand

the mechanisms that promote the coexistence of different life history

strategies

in temporally fluctuating and spatially heterogeneous environments.

Publications and

CV

amathias@u.arizona.edu

Back to top

Adam Miller

Spatial models of species coexistence

I study

mathematical models to understand how disturbance,

such

as

fire, affects species coexistence. Fire is known to be an

important factor in many ecological systems. In plant

communities, the combined effects of opening up space, burning biomass,

and releasing nutrients to the soil offer a variety of environmental

conditions. When burns are relatively frequent, and a stable burning

regime has persisted on evolutionary time scales, many species develop

specific responses to fires. Previous theory has shown that, when

species respond differently to environmental fluctuations, coexistence

can be promoted by certain types of interactions between environmental

and competitive factors. In this paper, we demonstrate how response

strategies to fire can form an axis of differentiation, allowing

species to stably coexist. In short, the action of differing fire

response strategies can generally provide a stabilizing storage

effect for the coexistence of species.

Maureen Ryan

Environmental

variation and species interactions

in

amphibian communities

I'm interested in how environmental variation promotes diversity within species and communities, and how mechanisms such as the storage effect that function through environmental variation can affect endangered species, in particular. My research focuses on a grassland salamander community in the Central Valley of California that includes the threatened California tiger salamander (Ambystoma californiense), hybrid tiger salamanders (A. californiense crossed with A. tigrinum mavortium, an introduced tiger salamander from the central US), and the California newt (Taricha torosa).

I'm using a combination of artificial pond experiments and field experiments to look at whether and how environmental variation promotes coexistence between the two native species, Ambystoma californiense and Taricha torosa, and how coexistence mechanisms operating in the native community are influenced by the addition of hybrid salamanders. Additionally, I'm looking at how environmental variation influences hybridization dynamics between A. cal iforniense and A. tigrinum mavortium and whether mechanisms associated with environmental variation can contribute to the maintenance of genetic polymorphism within hybridizing populations of tiger salamanders. Besides experiments, I'm using theoretical modeling and data from field surveys/sampling to investigate how dispersal and landscape structure interact with local community dynamics to influence species diversity and hybrid spread on a regional scale.

iforniense and A. tigrinum mavortium and whether mechanisms associated with environmental variation can contribute to the maintenance of genetic polymorphism within hybridizing populations of tiger salamanders. Besides experiments, I'm using theoretical modeling and data from field surveys/sampling to investigate how dispersal and landscape structure interact with local community dynamics to influence species diversity and hybrid spread on a regional scale.

From a conservation perspective, my work is motivated by an interest in how landscape alteration may influence amphibian diversity and species coexistence within extant communities, and in particular how common pond manipulations and the loss of vernal pools in the California Central Valley might influence California tiger salamander populations.

Anna Sears

Environmental variation and species interactions

Ecology is challenged to find simple ways to

understand the messiness of the natural world. I like to work from a

metacommunity

context, accepting that natural ecosystems contain a variety of

different

habitat types, and that this environmental variation affects the

interactions

of species within ecosystems. My PhD research specifically involves

using natural annual plant systems to test how variation in the

environment

affects species coexistence. I am also interested in how environmental

variation

affects food-web interactions, and generally interacts with other forms

of density

dependence. My field sites are in the Chihuahuan desert and at the

Bodega Marine

Reserve.

For my dissertation research, I studied how

spatial

variation in local density-dependent processes influences regional

dynamics. In collaboration with Marcel Holyoak, I investigated the

effects of local resource distribution, dispersal rate, and the

strength of density dependence on regional dynamics in a highly

manipulable microcosm system, in which we could track population

dynamics over time. Applying the same principles to a field system, I

studied Petrolisthes cinctipes,

a filter-feeding porcelain crab that lives in intertidal cobblefields

along the Pacific coast. Based out of Bodega Marine Laboratory, I

parameterized models of local density-dependence in this organism using

field and laboratory experiments. For Petrolisthes

cinctipes, the primary sources of density dependence are

gregarious settlement, competition, and predation. With Leah Akins, I

quantified the spatial variation that influences these process at two

scales: variation in P. cinctipes

density, predator abundance, and larval supply among rocks within sites

and among sites. By integrating information about spatial variation

into empirically-based models of local dynamics, we can predict what

local processes are most important when "scaling up" to regional

dynamics. For links to publications and Megan's CV, see her website.

My

main

research

interest is population dynamics,

especially how small-scale heterogeneity affects dynamics at larger

scales. Understanding how spatial and temporal heterogeneity affect the

dynamics of populations and communities is fundamental to ecology.

Indeed, answers to the most prominent questions in ecology involve the

pervasive influence of heterogeneity. Why do species coexist? Why are

there so many species? Why do some species cycle whereas others don't?

How does habitat fragmentation affect extinction?

Why are some species more invasive than others? Spatial and temporal

variation in population densities and in the physical environment are

essential considerations in these questions. My current research and

research to date focuses on the effects of spatial heterogeneity.

Whereas empirical studies have typically focused on heterogeneity

exclusively, theory demonstrates that population dynamics are altered

by spatial heterogeneity only when heterogeneity interacts with

nonlinear demographic processes - the pillar for research in the

Chesson lab. The aim of my research is to develop empirical tools to

measure the interaction

of nonlinearity and heterogeneity and to use these tools to probe real

populations.

Thus, I tackle the important issue of how to integrate theory and

models

with data from real systems, to understand how the interaction of

spatial

heterogeneity and nonlinearity alters population dynamics. I use these

insights

to address important basic and applied questions in ecology.

My

main

research

interest is population dynamics,

especially how small-scale heterogeneity affects dynamics at larger

scales. Understanding how spatial and temporal heterogeneity affect the

dynamics of populations and communities is fundamental to ecology.

Indeed, answers to the most prominent questions in ecology involve the

pervasive influence of heterogeneity. Why do species coexist? Why are

there so many species? Why do some species cycle whereas others don't?

How does habitat fragmentation affect extinction?

Why are some species more invasive than others? Spatial and temporal

variation in population densities and in the physical environment are

essential considerations in these questions. My current research and

research to date focuses on the effects of spatial heterogeneity.

Whereas empirical studies have typically focused on heterogeneity

exclusively, theory demonstrates that population dynamics are altered

by spatial heterogeneity only when heterogeneity interacts with

nonlinear demographic processes - the pillar for research in the

Chesson lab. The aim of my research is to develop empirical tools to

measure the interaction

of nonlinearity and heterogeneity and to use these tools to probe real

populations.

Thus, I tackle the important issue of how to integrate theory and

models

with data from real systems, to understand how the interaction of

spatial

heterogeneity and nonlinearity alters population dynamics. I use these

insights

to address important basic and applied questions in ecology.

bamelbourne@ucdavis.edu

Kendi Davies

The persistence

of species in patchy landscapes

The persistence

of species in patchy landscapes

My research focuses on testing and refining

theory

that makes predictions about the persistence of species in

heterogeneous landscapes, including metapopulation and related

spatio-temporal theory. So far, I have concentrated on the spatial and

temporal dynamics of populations and communities in landscapes that

have been modified by humans, through habitat fragmentation and

grazing. I am interested in how the life history characteristics of

species determine the response of species to landscape heterogeneity. I

use quantitative methods to test theory and have approached this work

using data from a large-scale, long-term field experiment for beetles

and data for a continental scale study of arid zone birds in Australia.

I am currently broadening this focus to explore

what

this same theory predicts about patterns of biological diversity in

naturally patchy

landscapes. I am focusing on the grassland plant community in

serpentine patches

in a non-serpentine matrix (in the University of California’s

McLaughlin Reserve).

Right now, I am particularly interested in spatial scale and the

relationship

between diversity and invasibility (Shea

and Chesson 2002).

Shea, K., Chesson, P. 2002. Community

ecology theory as a framework for biological invasions. Trends in

Ecology and Evolution 17, 170-176.

Some recent publications

Davies, K.F., Chesson, P., Harrison, S., Inouye, B.D.,

Melbourne,

B.A., Rice, K.J. 2005. Spatial heterogeneity explains the scale

dependence of the native-exotic diversity relationship. Ecology

86, 1602-1610.

Davies, K. F., C. R. Margules, and J. F.

Lawrence.

2004. A synergistic effect puts rare,

specialized species at greater risk of extinction. Ecology 85: 265-271.

Davies, K. F., B. A. Melbourne, C. R.

Margules,

and

J. F. Lawrence (in press).

Metacommunity structure influences the stability of local beetle

communities. In M.

Holyoak, M. A. Leibold and R. D. Holt eds. Metacommunities: Spatial

Dynamics and

Ecological Communities. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Davies, K. F., B. A. Melbourne, and C. R.

Margules.

2001. Effects

of within- and between-patch processes on community dynamics in a

fragmentation experiment. Ecology 82: 1830-1846.

Davies, K. F., C. Gascon, and C. R. Margules.

2001.

Habitat Fragmentation: consequences, management and future research

priorities. Pages 81-97 in M. E. Soulé and G. H. Orians,

editors. Conservation Biology: Research Priorities for the Next Decade.

Island Press, Washington.

Davies, K. F., C. R. Margules, and J. F.

Lawrence.

2000. Which

traits of species predict population declines in experimental forest

fragments? Ecology 81: 1450-1461.

Davies, K. F., and C. R. Margules. 1998.

Effects

of

habitat fragmentation on carabid beetles: experimental evidence.

Journal of Animal Ecology 67: 460-471.

Charlotte

Lee

Theory of multispecies

interactions; human-environment interactions

I study the theory of multispecies interactions,

with specific focus on

the matrix of coefficients for all pairwise interactions in a

community.

Specific projects include: 1) Determining relationships between

different

patterns of direct and indirect competitive (or facilitative)

interactions

and the structure of model community matrices; 2) determining patterns

of

shared resource use that result in specific community matrices; and 3)

developing techniques to do 1) and 2). I also study human-environment

interactions using theory from ecosystem ecology and demography.

Charlotte.Lee@stanford.edu

Friends of the Chesson Lab

collaborators from other labs

Scott Stark

Diversity maintenance in tropical plant communities

The classic gap hypothesis suggests

that canopy gaps promote forest

diversity by favoring the regeneration of tree species with high light

requirements (i.e., shade intolerant species). However, whether gaps

act to maintain forest diversity remains an unanswered question. We

argue that canopy gaps can promote coexistence between tree species

through the ‘storage effect.’ Certain combinations of environmental

conditions and species’ traits can advantage species when they are rare

and promote their long-term persistence in the community through the

‘storage effect.’ These combinations are likely to be found in canopy

gaps. For example, gaps (and subsequently light environments) vary in

both space and time and tree species appear to be differentiated in

terms of their ability to tolerate shade and respond to increases in

light. Furthermore, when gap environments are favorable to abundant

species their ability to increase in dominance is likely limited

(relative to rare species) because of increased within-species

competition (i.e., covariance of environmental favorability and

competition). Finally, rare species will likely persist even when

favorable gap conditions are infrequent because adult trees are

long-lived. We evaluate the ‘gap storage hypothesis’ with quantitative

analyses that incorporate realistic patterns of variation in light

environments (i.e., gaps) and trade-offs between species ability to

tolerate shade and grow in high light. We show that species

differentiated along this trade-off may coexist via the ‘storage

effect.’ We conclude that the ‘storage effect’ may act to maintain

forest diversity because of canopy gaps.

Yun Kang

In collaborating with the Chesson Lab,

I am particularly interested in

relative nonlinearity as a coexistence

mechanism. I work in other areas of mathematical biology modeling,

including nonlinear ecological models, stoichiometric ecology,

spatial ecology, and epidemiology. I have also studied random,

inhomogeneous, and dynamic graphs.

Yun.Kang@asu.edu

Community

Processes

in Variable Environments

Community

Processes

in Variable Environments

My

main

research

interest is population dynamics,

especially how small-scale heterogeneity affects dynamics at larger

scales. Understanding how spatial and temporal heterogeneity affect the

dynamics of populations and communities is fundamental to ecology.

Indeed, answers to the most prominent questions in ecology involve the

pervasive influence of heterogeneity. Why do species coexist? Why are

there so many species? Why do some species cycle whereas others don't?

How does habitat fragmentation affect extinction?

Why are some species more invasive than others? Spatial and temporal

variation in population densities and in the physical environment are

essential considerations in these questions. My current research and

research to date focuses on the effects of spatial heterogeneity.

Whereas empirical studies have typically focused on heterogeneity

exclusively, theory demonstrates that population dynamics are altered

by spatial heterogeneity only when heterogeneity interacts with

nonlinear demographic processes - the pillar for research in the

Chesson lab. The aim of my research is to develop empirical tools to

measure the interaction

of nonlinearity and heterogeneity and to use these tools to probe real

populations.

Thus, I tackle the important issue of how to integrate theory and

models

with data from real systems, to understand how the interaction of

spatial

heterogeneity and nonlinearity alters population dynamics. I use these

insights

to address important basic and applied questions in ecology.

My

main

research

interest is population dynamics,

especially how small-scale heterogeneity affects dynamics at larger

scales. Understanding how spatial and temporal heterogeneity affect the

dynamics of populations and communities is fundamental to ecology.

Indeed, answers to the most prominent questions in ecology involve the

pervasive influence of heterogeneity. Why do species coexist? Why are

there so many species? Why do some species cycle whereas others don't?

How does habitat fragmentation affect extinction?

Why are some species more invasive than others? Spatial and temporal

variation in population densities and in the physical environment are

essential considerations in these questions. My current research and

research to date focuses on the effects of spatial heterogeneity.

Whereas empirical studies have typically focused on heterogeneity

exclusively, theory demonstrates that population dynamics are altered

by spatial heterogeneity only when heterogeneity interacts with

nonlinear demographic processes - the pillar for research in the

Chesson lab. The aim of my research is to develop empirical tools to

measure the interaction

of nonlinearity and heterogeneity and to use these tools to probe real

populations.

Thus, I tackle the important issue of how to integrate theory and

models

with data from real systems, to understand how the interaction of

spatial

heterogeneity and nonlinearity alters population dynamics. I use these

insights

to address important basic and applied questions in ecology. The persistence

of species in patchy landscapes

The persistence

of species in patchy landscapes